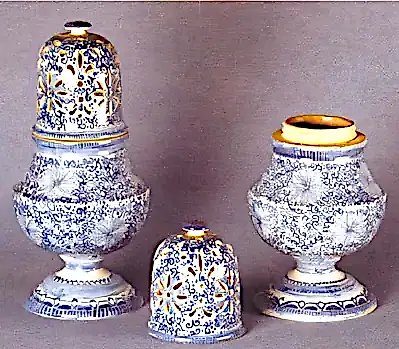

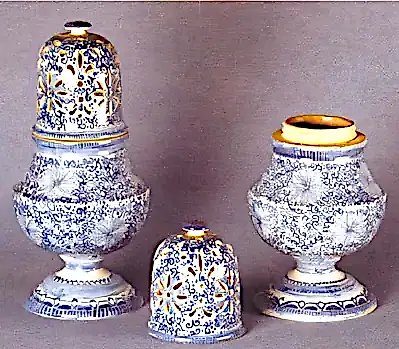

Have you ever wondered why antique Russian tableware features futuristic scenes, English austerity, or the colors of a Dutch rainbow? What lay behind the familiar plate with a bluish sheen – just simple kitchenware or a stamp of cultural revolution? Ceramics seem quiet and modest at first glance. But that's just a drawn curtain. Behind it: intertwined destinies, games of status, dazzling technological innovations, echoes of European fashion, and above all, the pulse of 19th-century Russia. Few know that the faience ware of Arkhangelskoye near Moscow is a hidden gem on the body of the vast country, blending French temperament, Russian talent, and ethereal English chic. *Items from the “Bellflower Service” (1829–1835)* *A candlestick, two teapots, and a cup with a saucer inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” (Arkhangelskoye Farm), 1827–1829* ## Let’s uncover this ornate artifact Prepare to be surprised: today you’ll see faience as a map of human passions and cultural codes. After this journey, even the simplest cup will never look the same. ### French Spark on Russian Soil: Auguste Lambert and Ceramics as Passion Imagine the early 19th century. The smell of molten metal, clay dust, bright French exclamations – all weaving into a strange dream among Russian snows. At Arkhangelskoye, the lavish Moscow estate of Prince Yusupov, where music plays and whispers of Europe’s fate are heard, a small faience factory suddenly starts working. Its inspirer: the Frenchman Auguste Philippe Lambert, an artist and painter from the legendary Sèvres manufactory. *Plate, milk jug, and lidded bowl, Arkhangelskoye Faience Factory, 1820s* At first, porcelain was attempted here, but debt, failures, and the eternal Russian question – where to find the best clays? – quickly shifted focus to the more accommodating but just as alluring faience. Lambert was not only a master but a visionary. He had what the French call “l’esprit aventureux” (adventurous spirit): an ability to spark interest in ceramics, seeing them as a world bridge. He organized the purchase of Gzhel clay, built kilns, assembled a chain of artisans, imported the best techniques from Europe, and experimented with decoration until he became entangled in debt enough to become a hero of his own business novel. His eyes were on England: he wanted Russian ware to rival the famous products of Staffordshire. Faience was then considered more democratic and "malleable" than porcelain. Unlike porcelain for grand ladies' gatherings, faience was a companion to turbulent, lively life: bought by both nobility and peasants. Customers came from all walks, and the range depended on the whims of capital and the changing times. In the shadows of the kiln, under the clatter of intricate machines, serf and free craftsmen created faience forms, trying to erase the boundary between Russian and European. *Items from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835* Lambert’s story is one of struggle for style, quality, and a unique face for Russian ceramics. His journey was rocky—first an attempt at porcelain, then a faience rebirth, debts, partnerships, a shuffling of German and French models, death, and the enterprise passing to his widow and new partners. In every cup and tureen is an imprint of this human drama: determination, failure, and the rearrangement of priorities. #### A Transition to Secret Knowledge. Why does it all matter? Looking into the fate of Arkhangelskoye faience reveals an intersection not only of people but of epochs: Russia striving to break free from English ceramic influence, Europe tiptoeing around fashion, and the unique Russian potential. Here, faience is far more than kitchenware. It is a social experiment, an attempt to overcome provincialism through aesthetics. *Tureen (soup tureen) from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835; Mark "LAMBERT" impressed in the body, found on the “Bellflower Service” and plates with the portrait of the Duchess of Courland, 1827–1835; Tureen, English Faience, Wedgwood Factory* The echoes of that struggle are felt even today. Modern interior design loves to reinvent the past: cafés styled after “19th-century France,” luxurious services with supposedly authentic shine. The trend for "handcrafted" goods, for mixes of traditions, for cross-cultural products – all this has roots in the distant workshop of Arkhangelskoye. #### “Arkhangelskoye Farm” and the Sacred Geography of Faience Let’s delve into the factory’s walls – where the past remains tangible. Did anything survive from what Lambert’s artisans once shaped and painted? *Decorative sculpture and covered bowl (compote dish?) inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* Yes, not only fragments but whole services, entire visual stories remain. The factory's pride—the famed “Bellflower Service” (actually featuring lotus fruits, but who counts!)—showcased delicate faience once admired only in England. Here are grand tureens with volute handles, lidded bowls adorned with sculpted pears, milk jugs of thick, porous body imitating German and French majolica... All this diversity feels chaotic, yet is aesthetically unified and refined. Adornments of English, Dutch, French, and even Chinese factories are not merely copied, but reinterpreted. Each pattern gains new Russian meaning. Plates with green-brown glaze evoke the British fashion for “tortoiseshell” imitation; cups marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” hint at the idea of local branding; pots and salt cellars recall the handmade craft bordering on naïve art. *Plate with the portrait of E.B. Biron, Duchess of Courland, née Princess Yusupova. 1827 – 1835. After an engraving by J. Houbraken, 1775.* Here’s the paradox: in this seemingly cosmopolitan art, the faience cup held a Russian spirit. Even if its form was stolen from an English queen’s catalog or its decor borrowed from Delft masters, the very fact of faience being made in a Russian estate was already a revolution against dependence. Every new item—a small triumph over external fashion. Athin side, an elegantly bent handle, a polychrome border, a recognizable inscription—all say: “Yes, Russia can do it too!” *Delft faience, late 18th century. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.* The story of the service labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” is a web of marking, localization, and cultural self-respect. In every detail is a graft of style, an effort to show Russian masters can have their own grand table, their own pride—no worse than the Europeans. Viewed today, we call this an author’s style, a local product, a small batch. But when we see an old cup from Arkhangelskoye, we marvel: the trend for branded goods, for micro-studios, for individual runs and collaborations—began here, more than a hundred years ago. ### Through the Looking Glass: Symbols, Inscriptions, and the True Psychology of Art Let’s talk about the psychology of perception. Why do we love faience so much? Why can an old plate, decorated with an unnecessarily intricate border and impractical inscription, spark delight? Everything matters here: the right color of the body, the slightly translucent glaze, the highlighted Latin script—"LAMBERT", "ROMARINO", "ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA." *Plates labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* What’s special here? A person of the 19th century, much like us today, sought authenticity in small things. It is in the strokes that they recognized the true author, the real work; by the stamp they determined not only the technique but the potter’s integrity. The pursuit of true mastery always goes hand in hand with a thirst to experiment. *Sugar containers labeled ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA, 1827–1829; their forms repeat similar items from Rouen faience of the late 17th century from the Paris Museum of Decorative Arts. Pâté dish with lid in the form of two pigeons. Inscription on reverse: “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* The marks and symbols of the Arkhangelskoye factory held both imitation (traits of the Delft school, mystical letters and numbers, direct quotations from European workshops) and protest—a literal Russian inscription as a sign of genuine independence, certification of their achievements. Thus, a split between imitation and self-sufficiency. Symbolism in the details: each tureen handle echoes the debate between laborious beauty and new order, each relief flower signs the striving to live beautifully, but in a Russian way. Faience tableware ceases being utilitarian and becomes a status marker, a symbol of heroic struggle for independent art. This game of cultural codes only heightens the appeal. Intricate underglaze patterns and pronounced baroqueness are not merely a nod to Western fashion but—viewed from the 21st century—the first version of “cultural identity”: to be on trend, but not lose oneself. Lambert’s craftsmen could create items worth preserving—as an epoch's snapshot. *Oyster dish, two butter dishes with covers as pigeons in a nest, and a salt cellar marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* #### The Mystery of Disappearance and Revival of Interest Lambert’s production was small and, it seemed, insignificant for vast Russia. Few items survived—many lost with time, ruined, dispersed among collections, stripped of markings… After Lambert’s death, others ran the factory; new names appeared, and only some pieces were signed in Russian, some in Latin, most now easily confused with Western European faience. The tale often ends where inscriptions fade. *Cup and saucer from the ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA service, 1827–1829.* But as is always the case with true art, revival is only a matter of time. Today, the value of Arkhangelskoye faience lies not only in its rarity. It is a symbol of cultural synthesis, a craft history where there are no losers—only the evolution of taste. Parisian cafés order handmade tableware from Russia, street artists use color schemes of old services, designers seek new identities inspired by ornaments of bygone eras. *Reverse of a salt cellar labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” and imitation of a Delft factory “Two Boats” mark, 1827–1829* **What should we do with this knowledge?** Next time, whether at the table or in an antique shop, try picking up something handmade, even if a bit rough. Listen to its story: perhaps it’s not just pottery but a coded message from an era of daring, deprivation, and grand encounters. *Decorative vase and tulip vases inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829.* Behind the gentle shine of faience is a continent of passion, change, and cultural discoveries. Some sought genuine England in a Russian cup, others tried to outdo European chic, others simply survived—thus creating something unique. The story of Yusupov-Lambert faience is a tale of interweaving, searching, and daring hope to make life a little more beautiful, and the country a little more independent. What story hides in your favorite cup? Could you continue the chain of inspiration started two hundred years ago in the dusty workshop of Arkhangelskoye?

Have you ever wondered why antique Russian tableware features futuristic scenes, English austerity, or the colors of a Dutch rainbow? What lay behind the familiar plate with a bluish sheen – just simple kitchenware or a stamp of cultural revolution? Ceramics seem quiet and modest at first glance. But that's just a drawn curtain. Behind it: intertwined destinies, games of status, dazzling technological innovations, echoes of European fashion, and above all, the pulse of 19th-century Russia. Few know that the faience ware of Arkhangelskoye near Moscow is a hidden gem on the body of the vast country, blending French temperament, Russian talent, and ethereal English chic. *Items from the “Bellflower Service” (1829–1835)* *A candlestick, two teapots, and a cup with a saucer inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” (Arkhangelskoye Farm), 1827–1829* ## Let’s uncover this ornate artifact Prepare to be surprised: today you’ll see faience as a map of human passions and cultural codes. After this journey, even the simplest cup will never look the same. ### French Spark on Russian Soil: Auguste Lambert and Ceramics as Passion Imagine the early 19th century. The smell of molten metal, clay dust, bright French exclamations – all weaving into a strange dream among Russian snows. At Arkhangelskoye, the lavish Moscow estate of Prince Yusupov, where music plays and whispers of Europe’s fate are heard, a small faience factory suddenly starts working. Its inspirer: the Frenchman Auguste Philippe Lambert, an artist and painter from the legendary Sèvres manufactory. *Plate, milk jug, and lidded bowl, Arkhangelskoye Faience Factory, 1820s* At first, porcelain was attempted here, but debt, failures, and the eternal Russian question – where to find the best clays? – quickly shifted focus to the more accommodating but just as alluring faience. Lambert was not only a master but a visionary. He had what the French call “l’esprit aventureux” (adventurous spirit): an ability to spark interest in ceramics, seeing them as a world bridge. He organized the purchase of Gzhel clay, built kilns, assembled a chain of artisans, imported the best techniques from Europe, and experimented with decoration until he became entangled in debt enough to become a hero of his own business novel. His eyes were on England: he wanted Russian ware to rival the famous products of Staffordshire. Faience was then considered more democratic and "malleable" than porcelain. Unlike porcelain for grand ladies' gatherings, faience was a companion to turbulent, lively life: bought by both nobility and peasants. Customers came from all walks, and the range depended on the whims of capital and the changing times. In the shadows of the kiln, under the clatter of intricate machines, serf and free craftsmen created faience forms, trying to erase the boundary between Russian and European. *Items from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835* Lambert’s story is one of struggle for style, quality, and a unique face for Russian ceramics. His journey was rocky—first an attempt at porcelain, then a faience rebirth, debts, partnerships, a shuffling of German and French models, death, and the enterprise passing to his widow and new partners. In every cup and tureen is an imprint of this human drama: determination, failure, and the rearrangement of priorities. #### A Transition to Secret Knowledge. Why does it all matter? Looking into the fate of Arkhangelskoye faience reveals an intersection not only of people but of epochs: Russia striving to break free from English ceramic influence, Europe tiptoeing around fashion, and the unique Russian potential. Here, faience is far more than kitchenware. It is a social experiment, an attempt to overcome provincialism through aesthetics. *Tureen (soup tureen) from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835; Mark "LAMBERT" impressed in the body, found on the “Bellflower Service” and plates with the portrait of the Duchess of Courland, 1827–1835; Tureen, English Faience, Wedgwood Factory* The echoes of that struggle are felt even today. Modern interior design loves to reinvent the past: cafés styled after “19th-century France,” luxurious services with supposedly authentic shine. The trend for "handcrafted" goods, for mixes of traditions, for cross-cultural products – all this has roots in the distant workshop of Arkhangelskoye. #### “Arkhangelskoye Farm” and the Sacred Geography of Faience Let’s delve into the factory’s walls – where the past remains tangible. Did anything survive from what Lambert’s artisans once shaped and painted? *Decorative sculpture and covered bowl (compote dish?) inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* Yes, not only fragments but whole services, entire visual stories remain. The factory's pride—the famed “Bellflower Service” (actually featuring lotus fruits, but who counts!)—showcased delicate faience once admired only in England. Here are grand tureens with volute handles, lidded bowls adorned with sculpted pears, milk jugs of thick, porous body imitating German and French majolica... All this diversity feels chaotic, yet is aesthetically unified and refined. Adornments of English, Dutch, French, and even Chinese factories are not merely copied, but reinterpreted. Each pattern gains new Russian meaning. Plates with green-brown glaze evoke the British fashion for “tortoiseshell” imitation; cups marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” hint at the idea of local branding; pots and salt cellars recall the handmade craft bordering on naïve art. *Plate with the portrait of E.B. Biron, Duchess of Courland, née Princess Yusupova. 1827 – 1835. After an engraving by J. Houbraken, 1775.* Here’s the paradox: in this seemingly cosmopolitan art, the faience cup held a Russian spirit. Even if its form was stolen from an English queen’s catalog or its decor borrowed from Delft masters, the very fact of faience being made in a Russian estate was already a revolution against dependence. Every new item—a small triumph over external fashion. Athin side, an elegantly bent handle, a polychrome border, a recognizable inscription—all say: “Yes, Russia can do it too!” *Delft faience, late 18th century. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.* The story of the service labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” is a web of marking, localization, and cultural self-respect. In every detail is a graft of style, an effort to show Russian masters can have their own grand table, their own pride—no worse than the Europeans. Viewed today, we call this an author’s style, a local product, a small batch. But when we see an old cup from Arkhangelskoye, we marvel: the trend for branded goods, for micro-studios, for individual runs and collaborations—began here, more than a hundred years ago. ### Through the Looking Glass: Symbols, Inscriptions, and the True Psychology of Art Let’s talk about the psychology of perception. Why do we love faience so much? Why can an old plate, decorated with an unnecessarily intricate border and impractical inscription, spark delight? Everything matters here: the right color of the body, the slightly translucent glaze, the highlighted Latin script—"LAMBERT", "ROMARINO", "ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA." *Plates labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* What’s special here? A person of the 19th century, much like us today, sought authenticity in small things. It is in the strokes that they recognized the true author, the real work; by the stamp they determined not only the technique but the potter’s integrity. The pursuit of true mastery always goes hand in hand with a thirst to experiment. *Sugar containers labeled ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA, 1827–1829; their forms repeat similar items from Rouen faience of the late 17th century from the Paris Museum of Decorative Arts. Pâté dish with lid in the form of two pigeons. Inscription on reverse: “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* The marks and symbols of the Arkhangelskoye factory held both imitation (traits of the Delft school, mystical letters and numbers, direct quotations from European workshops) and protest—a literal Russian inscription as a sign of genuine independence, certification of their achievements. Thus, a split between imitation and self-sufficiency. Symbolism in the details: each tureen handle echoes the debate between laborious beauty and new order, each relief flower signs the striving to live beautifully, but in a Russian way. Faience tableware ceases being utilitarian and becomes a status marker, a symbol of heroic struggle for independent art. This game of cultural codes only heightens the appeal. Intricate underglaze patterns and pronounced baroqueness are not merely a nod to Western fashion but—viewed from the 21st century—the first version of “cultural identity”: to be on trend, but not lose oneself. Lambert’s craftsmen could create items worth preserving—as an epoch's snapshot. *Oyster dish, two butter dishes with covers as pigeons in a nest, and a salt cellar marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* #### The Mystery of Disappearance and Revival of Interest Lambert’s production was small and, it seemed, insignificant for vast Russia. Few items survived—many lost with time, ruined, dispersed among collections, stripped of markings… After Lambert’s death, others ran the factory; new names appeared, and only some pieces were signed in Russian, some in Latin, most now easily confused with Western European faience. The tale often ends where inscriptions fade. *Cup and saucer from the ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA service, 1827–1829.* But as is always the case with true art, revival is only a matter of time. Today, the value of Arkhangelskoye faience lies not only in its rarity. It is a symbol of cultural synthesis, a craft history where there are no losers—only the evolution of taste. Parisian cafés order handmade tableware from Russia, street artists use color schemes of old services, designers seek new identities inspired by ornaments of bygone eras. *Reverse of a salt cellar labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” and imitation of a Delft factory “Two Boats” mark, 1827–1829* **What should we do with this knowledge?** Next time, whether at the table or in an antique shop, try picking up something handmade, even if a bit rough. Listen to its story: perhaps it’s not just pottery but a coded message from an era of daring, deprivation, and grand encounters. *Decorative vase and tulip vases inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829.* Behind the gentle shine of faience is a continent of passion, change, and cultural discoveries. Some sought genuine England in a Russian cup, others tried to outdo European chic, others simply survived—thus creating something unique. The story of Yusupov-Lambert faience is a tale of interweaving, searching, and daring hope to make life a little more beautiful, and the country a little more independent. What story hides in your favorite cup? Could you continue the chain of inspiration started two hundred years ago in the dusty workshop of Arkhangelskoye?How a Frenchman and Debt Changed the Ceramic Face of Russia

Have you ever wondered why antique Russian tableware features futuristic scenes, English austerity, or the colors of a Dutch rainbow? What lay behind the familiar plate with a bluish sheen – just simple kitchenware or a stamp of cultural revolution? Ceramics seem quiet and modest at first glance. But that's just a drawn curtain. Behind it: intertwined destinies, games of status, dazzling technological innovations, echoes of European fashion, and above all, the pulse of 19th-century Russia. Few know that the faience ware of Arkhangelskoye near Moscow is a hidden gem on the body of the vast country, blending French temperament, Russian talent, and ethereal English chic. *Items from the “Bellflower Service” (1829–1835)* *A candlestick, two teapots, and a cup with a saucer inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” (Arkhangelskoye Farm), 1827–1829* ## Let’s uncover this ornate artifact Prepare to be surprised: today you’ll see faience as a map of human passions and cultural codes. After this journey, even the simplest cup will never look the same. ### French Spark on Russian Soil: Auguste Lambert and Ceramics as Passion Imagine the early 19th century. The smell of molten metal, clay dust, bright French exclamations – all weaving into a strange dream among Russian snows. At Arkhangelskoye, the lavish Moscow estate of Prince Yusupov, where music plays and whispers of Europe’s fate are heard, a small faience factory suddenly starts working. Its inspirer: the Frenchman Auguste Philippe Lambert, an artist and painter from the legendary Sèvres manufactory. *Plate, milk jug, and lidded bowl, Arkhangelskoye Faience Factory, 1820s* At first, porcelain was attempted here, but debt, failures, and the eternal Russian question – where to find the best clays? – quickly shifted focus to the more accommodating but just as alluring faience. Lambert was not only a master but a visionary. He had what the French call “l’esprit aventureux” (adventurous spirit): an ability to spark interest in ceramics, seeing them as a world bridge. He organized the purchase of Gzhel clay, built kilns, assembled a chain of artisans, imported the best techniques from Europe, and experimented with decoration until he became entangled in debt enough to become a hero of his own business novel. His eyes were on England: he wanted Russian ware to rival the famous products of Staffordshire. Faience was then considered more democratic and "malleable" than porcelain. Unlike porcelain for grand ladies' gatherings, faience was a companion to turbulent, lively life: bought by both nobility and peasants. Customers came from all walks, and the range depended on the whims of capital and the changing times. In the shadows of the kiln, under the clatter of intricate machines, serf and free craftsmen created faience forms, trying to erase the boundary between Russian and European. *Items from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835* Lambert’s story is one of struggle for style, quality, and a unique face for Russian ceramics. His journey was rocky—first an attempt at porcelain, then a faience rebirth, debts, partnerships, a shuffling of German and French models, death, and the enterprise passing to his widow and new partners. In every cup and tureen is an imprint of this human drama: determination, failure, and the rearrangement of priorities. #### A Transition to Secret Knowledge. Why does it all matter? Looking into the fate of Arkhangelskoye faience reveals an intersection not only of people but of epochs: Russia striving to break free from English ceramic influence, Europe tiptoeing around fashion, and the unique Russian potential. Here, faience is far more than kitchenware. It is a social experiment, an attempt to overcome provincialism through aesthetics. *Tureen (soup tureen) from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835; Mark "LAMBERT" impressed in the body, found on the “Bellflower Service” and plates with the portrait of the Duchess of Courland, 1827–1835; Tureen, English Faience, Wedgwood Factory* The echoes of that struggle are felt even today. Modern interior design loves to reinvent the past: cafés styled after “19th-century France,” luxurious services with supposedly authentic shine. The trend for "handcrafted" goods, for mixes of traditions, for cross-cultural products – all this has roots in the distant workshop of Arkhangelskoye. #### “Arkhangelskoye Farm” and the Sacred Geography of Faience Let’s delve into the factory’s walls – where the past remains tangible. Did anything survive from what Lambert’s artisans once shaped and painted? *Decorative sculpture and covered bowl (compote dish?) inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* Yes, not only fragments but whole services, entire visual stories remain. The factory's pride—the famed “Bellflower Service” (actually featuring lotus fruits, but who counts!)—showcased delicate faience once admired only in England. Here are grand tureens with volute handles, lidded bowls adorned with sculpted pears, milk jugs of thick, porous body imitating German and French majolica... All this diversity feels chaotic, yet is aesthetically unified and refined. Adornments of English, Dutch, French, and even Chinese factories are not merely copied, but reinterpreted. Each pattern gains new Russian meaning. Plates with green-brown glaze evoke the British fashion for “tortoiseshell” imitation; cups marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” hint at the idea of local branding; pots and salt cellars recall the handmade craft bordering on naïve art. *Plate with the portrait of E.B. Biron, Duchess of Courland, née Princess Yusupova. 1827 – 1835. After an engraving by J. Houbraken, 1775.* Here’s the paradox: in this seemingly cosmopolitan art, the faience cup held a Russian spirit. Even if its form was stolen from an English queen’s catalog or its decor borrowed from Delft masters, the very fact of faience being made in a Russian estate was already a revolution against dependence. Every new item—a small triumph over external fashion. Athin side, an elegantly bent handle, a polychrome border, a recognizable inscription—all say: “Yes, Russia can do it too!” *Delft faience, late 18th century. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.* The story of the service labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” is a web of marking, localization, and cultural self-respect. In every detail is a graft of style, an effort to show Russian masters can have their own grand table, their own pride—no worse than the Europeans. Viewed today, we call this an author’s style, a local product, a small batch. But when we see an old cup from Arkhangelskoye, we marvel: the trend for branded goods, for micro-studios, for individual runs and collaborations—began here, more than a hundred years ago. ### Through the Looking Glass: Symbols, Inscriptions, and the True Psychology of Art Let’s talk about the psychology of perception. Why do we love faience so much? Why can an old plate, decorated with an unnecessarily intricate border and impractical inscription, spark delight? Everything matters here: the right color of the body, the slightly translucent glaze, the highlighted Latin script—"LAMBERT", "ROMARINO", "ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA." *Plates labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* What’s special here? A person of the 19th century, much like us today, sought authenticity in small things. It is in the strokes that they recognized the true author, the real work; by the stamp they determined not only the technique but the potter’s integrity. The pursuit of true mastery always goes hand in hand with a thirst to experiment. *Sugar containers labeled ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA, 1827–1829; their forms repeat similar items from Rouen faience of the late 17th century from the Paris Museum of Decorative Arts. Pâté dish with lid in the form of two pigeons. Inscription on reverse: “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* The marks and symbols of the Arkhangelskoye factory held both imitation (traits of the Delft school, mystical letters and numbers, direct quotations from European workshops) and protest—a literal Russian inscription as a sign of genuine independence, certification of their achievements. Thus, a split between imitation and self-sufficiency. Symbolism in the details: each tureen handle echoes the debate between laborious beauty and new order, each relief flower signs the striving to live beautifully, but in a Russian way. Faience tableware ceases being utilitarian and becomes a status marker, a symbol of heroic struggle for independent art. This game of cultural codes only heightens the appeal. Intricate underglaze patterns and pronounced baroqueness are not merely a nod to Western fashion but—viewed from the 21st century—the first version of “cultural identity”: to be on trend, but not lose oneself. Lambert’s craftsmen could create items worth preserving—as an epoch's snapshot. *Oyster dish, two butter dishes with covers as pigeons in a nest, and a salt cellar marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* #### The Mystery of Disappearance and Revival of Interest Lambert’s production was small and, it seemed, insignificant for vast Russia. Few items survived—many lost with time, ruined, dispersed among collections, stripped of markings… After Lambert’s death, others ran the factory; new names appeared, and only some pieces were signed in Russian, some in Latin, most now easily confused with Western European faience. The tale often ends where inscriptions fade. *Cup and saucer from the ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA service, 1827–1829.* But as is always the case with true art, revival is only a matter of time. Today, the value of Arkhangelskoye faience lies not only in its rarity. It is a symbol of cultural synthesis, a craft history where there are no losers—only the evolution of taste. Parisian cafés order handmade tableware from Russia, street artists use color schemes of old services, designers seek new identities inspired by ornaments of bygone eras. *Reverse of a salt cellar labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” and imitation of a Delft factory “Two Boats” mark, 1827–1829* **What should we do with this knowledge?** Next time, whether at the table or in an antique shop, try picking up something handmade, even if a bit rough. Listen to its story: perhaps it’s not just pottery but a coded message from an era of daring, deprivation, and grand encounters. *Decorative vase and tulip vases inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829.* Behind the gentle shine of faience is a continent of passion, change, and cultural discoveries. Some sought genuine England in a Russian cup, others tried to outdo European chic, others simply survived—thus creating something unique. The story of Yusupov-Lambert faience is a tale of interweaving, searching, and daring hope to make life a little more beautiful, and the country a little more independent. What story hides in your favorite cup? Could you continue the chain of inspiration started two hundred years ago in the dusty workshop of Arkhangelskoye?

Have you ever wondered why antique Russian tableware features futuristic scenes, English austerity, or the colors of a Dutch rainbow? What lay behind the familiar plate with a bluish sheen – just simple kitchenware or a stamp of cultural revolution? Ceramics seem quiet and modest at first glance. But that's just a drawn curtain. Behind it: intertwined destinies, games of status, dazzling technological innovations, echoes of European fashion, and above all, the pulse of 19th-century Russia. Few know that the faience ware of Arkhangelskoye near Moscow is a hidden gem on the body of the vast country, blending French temperament, Russian talent, and ethereal English chic. *Items from the “Bellflower Service” (1829–1835)* *A candlestick, two teapots, and a cup with a saucer inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” (Arkhangelskoye Farm), 1827–1829* ## Let’s uncover this ornate artifact Prepare to be surprised: today you’ll see faience as a map of human passions and cultural codes. After this journey, even the simplest cup will never look the same. ### French Spark on Russian Soil: Auguste Lambert and Ceramics as Passion Imagine the early 19th century. The smell of molten metal, clay dust, bright French exclamations – all weaving into a strange dream among Russian snows. At Arkhangelskoye, the lavish Moscow estate of Prince Yusupov, where music plays and whispers of Europe’s fate are heard, a small faience factory suddenly starts working. Its inspirer: the Frenchman Auguste Philippe Lambert, an artist and painter from the legendary Sèvres manufactory. *Plate, milk jug, and lidded bowl, Arkhangelskoye Faience Factory, 1820s* At first, porcelain was attempted here, but debt, failures, and the eternal Russian question – where to find the best clays? – quickly shifted focus to the more accommodating but just as alluring faience. Lambert was not only a master but a visionary. He had what the French call “l’esprit aventureux” (adventurous spirit): an ability to spark interest in ceramics, seeing them as a world bridge. He organized the purchase of Gzhel clay, built kilns, assembled a chain of artisans, imported the best techniques from Europe, and experimented with decoration until he became entangled in debt enough to become a hero of his own business novel. His eyes were on England: he wanted Russian ware to rival the famous products of Staffordshire. Faience was then considered more democratic and "malleable" than porcelain. Unlike porcelain for grand ladies' gatherings, faience was a companion to turbulent, lively life: bought by both nobility and peasants. Customers came from all walks, and the range depended on the whims of capital and the changing times. In the shadows of the kiln, under the clatter of intricate machines, serf and free craftsmen created faience forms, trying to erase the boundary between Russian and European. *Items from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835* Lambert’s story is one of struggle for style, quality, and a unique face for Russian ceramics. His journey was rocky—first an attempt at porcelain, then a faience rebirth, debts, partnerships, a shuffling of German and French models, death, and the enterprise passing to his widow and new partners. In every cup and tureen is an imprint of this human drama: determination, failure, and the rearrangement of priorities. #### A Transition to Secret Knowledge. Why does it all matter? Looking into the fate of Arkhangelskoye faience reveals an intersection not only of people but of epochs: Russia striving to break free from English ceramic influence, Europe tiptoeing around fashion, and the unique Russian potential. Here, faience is far more than kitchenware. It is a social experiment, an attempt to overcome provincialism through aesthetics. *Tureen (soup tureen) from the “Bellflower Service,” 1829–1835; Mark "LAMBERT" impressed in the body, found on the “Bellflower Service” and plates with the portrait of the Duchess of Courland, 1827–1835; Tureen, English Faience, Wedgwood Factory* The echoes of that struggle are felt even today. Modern interior design loves to reinvent the past: cafés styled after “19th-century France,” luxurious services with supposedly authentic shine. The trend for "handcrafted" goods, for mixes of traditions, for cross-cultural products – all this has roots in the distant workshop of Arkhangelskoye. #### “Arkhangelskoye Farm” and the Sacred Geography of Faience Let’s delve into the factory’s walls – where the past remains tangible. Did anything survive from what Lambert’s artisans once shaped and painted? *Decorative sculpture and covered bowl (compote dish?) inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* Yes, not only fragments but whole services, entire visual stories remain. The factory's pride—the famed “Bellflower Service” (actually featuring lotus fruits, but who counts!)—showcased delicate faience once admired only in England. Here are grand tureens with volute handles, lidded bowls adorned with sculpted pears, milk jugs of thick, porous body imitating German and French majolica... All this diversity feels chaotic, yet is aesthetically unified and refined. Adornments of English, Dutch, French, and even Chinese factories are not merely copied, but reinterpreted. Each pattern gains new Russian meaning. Plates with green-brown glaze evoke the British fashion for “tortoiseshell” imitation; cups marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” hint at the idea of local branding; pots and salt cellars recall the handmade craft bordering on naïve art. *Plate with the portrait of E.B. Biron, Duchess of Courland, née Princess Yusupova. 1827 – 1835. After an engraving by J. Houbraken, 1775.* Here’s the paradox: in this seemingly cosmopolitan art, the faience cup held a Russian spirit. Even if its form was stolen from an English queen’s catalog or its decor borrowed from Delft masters, the very fact of faience being made in a Russian estate was already a revolution against dependence. Every new item—a small triumph over external fashion. Athin side, an elegantly bent handle, a polychrome border, a recognizable inscription—all say: “Yes, Russia can do it too!” *Delft faience, late 18th century. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.* The story of the service labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” is a web of marking, localization, and cultural self-respect. In every detail is a graft of style, an effort to show Russian masters can have their own grand table, their own pride—no worse than the Europeans. Viewed today, we call this an author’s style, a local product, a small batch. But when we see an old cup from Arkhangelskoye, we marvel: the trend for branded goods, for micro-studios, for individual runs and collaborations—began here, more than a hundred years ago. ### Through the Looking Glass: Symbols, Inscriptions, and the True Psychology of Art Let’s talk about the psychology of perception. Why do we love faience so much? Why can an old plate, decorated with an unnecessarily intricate border and impractical inscription, spark delight? Everything matters here: the right color of the body, the slightly translucent glaze, the highlighted Latin script—"LAMBERT", "ROMARINO", "ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA." *Plates labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* What’s special here? A person of the 19th century, much like us today, sought authenticity in small things. It is in the strokes that they recognized the true author, the real work; by the stamp they determined not only the technique but the potter’s integrity. The pursuit of true mastery always goes hand in hand with a thirst to experiment. *Sugar containers labeled ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA, 1827–1829; their forms repeat similar items from Rouen faience of the late 17th century from the Paris Museum of Decorative Arts. Pâté dish with lid in the form of two pigeons. Inscription on reverse: “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* The marks and symbols of the Arkhangelskoye factory held both imitation (traits of the Delft school, mystical letters and numbers, direct quotations from European workshops) and protest—a literal Russian inscription as a sign of genuine independence, certification of their achievements. Thus, a split between imitation and self-sufficiency. Symbolism in the details: each tureen handle echoes the debate between laborious beauty and new order, each relief flower signs the striving to live beautifully, but in a Russian way. Faience tableware ceases being utilitarian and becomes a status marker, a symbol of heroic struggle for independent art. This game of cultural codes only heightens the appeal. Intricate underglaze patterns and pronounced baroqueness are not merely a nod to Western fashion but—viewed from the 21st century—the first version of “cultural identity”: to be on trend, but not lose oneself. Lambert’s craftsmen could create items worth preserving—as an epoch's snapshot. *Oyster dish, two butter dishes with covers as pigeons in a nest, and a salt cellar marked “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829* #### The Mystery of Disappearance and Revival of Interest Lambert’s production was small and, it seemed, insignificant for vast Russia. Few items survived—many lost with time, ruined, dispersed among collections, stripped of markings… After Lambert’s death, others ran the factory; new names appeared, and only some pieces were signed in Russian, some in Latin, most now easily confused with Western European faience. The tale often ends where inscriptions fade. *Cup and saucer from the ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA service, 1827–1829.* But as is always the case with true art, revival is only a matter of time. Today, the value of Arkhangelskoye faience lies not only in its rarity. It is a symbol of cultural synthesis, a craft history where there are no losers—only the evolution of taste. Parisian cafés order handmade tableware from Russia, street artists use color schemes of old services, designers seek new identities inspired by ornaments of bygone eras. *Reverse of a salt cellar labeled “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA” and imitation of a Delft factory “Two Boats” mark, 1827–1829* **What should we do with this knowledge?** Next time, whether at the table or in an antique shop, try picking up something handmade, even if a bit rough. Listen to its story: perhaps it’s not just pottery but a coded message from an era of daring, deprivation, and grand encounters. *Decorative vase and tulip vases inscribed “ARKHANGELSKAYA FERMA”, 1827–1829.* Behind the gentle shine of faience is a continent of passion, change, and cultural discoveries. Some sought genuine England in a Russian cup, others tried to outdo European chic, others simply survived—thus creating something unique. The story of Yusupov-Lambert faience is a tale of interweaving, searching, and daring hope to make life a little more beautiful, and the country a little more independent. What story hides in your favorite cup? Could you continue the chain of inspiration started two hundred years ago in the dusty workshop of Arkhangelskoye?Auction of works of art and antiques art-picture.ru provides the opportunity to purchase

purchase lots on the topic are presented "How a Frenchman and Debt Changed the Ceramic Face of Russia"

Imperial Porcelain and the Lost Masterpieces of Baron Rausch

What can a porcelain horseman tell us?Have you ever let your gaze linger o…

The Secret of Napoleon's Porcelain Olympus

A Keyhole Into Another WorldHave you ever thought about an object created …

Фарфоровая судьба: Когда банальность становится искусством

Длительное время этот скульптор трудился на посту главного модельмейстер…

What is porcelain

Porcelain tableware and other porcelain items have served as a symbol of w…

Porcelain figurines

Porcelain figurines are beautiful and exquisite decorative items that have…

Meissen porcelain

Meissen is a German city known for its porcelain products. Meissen porcela…

KPM plates (Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur) from Germany

KPM (Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur) is the oldest porcelain manufactory…

Bing & Grondahl factory figurines

The Bing & Grondahl factory was founded in 1853 in Copenhagen, Denmark…