Русская национальная конница в Лейпцигском сражении

Русская национальная конница в Лейпцигском сражении

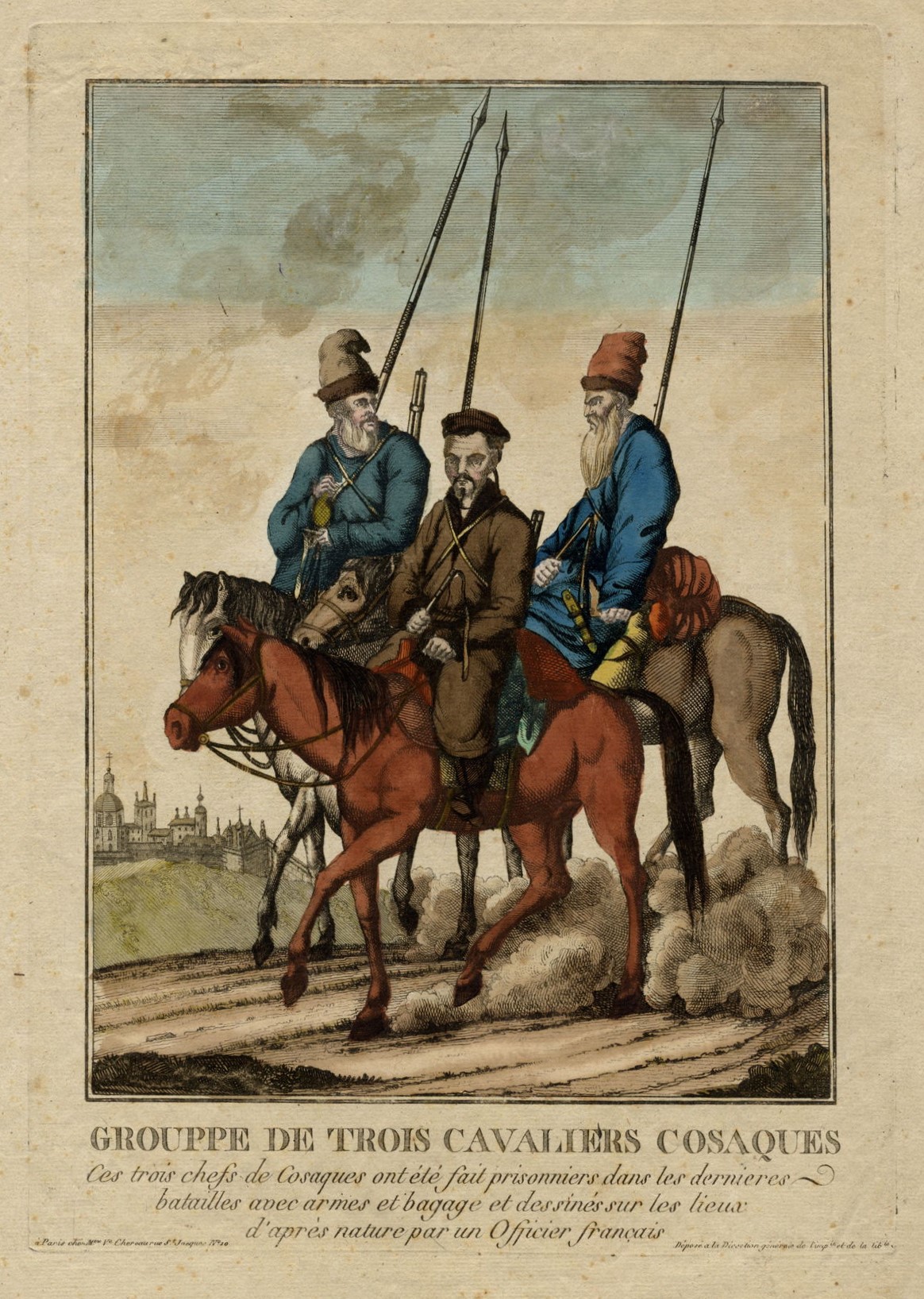

В отделе изобразительных материалов Государственного исторического музея среди графических листов, посвященных событиям эпохи 1812 года, отдельное место принадлежит изображениям иррегулярных частей, участвовавших в Отечественной войне 1812 года и Заграничных походах 1813–1814 гг. Гравюры с изображением казаков, калмыков, татар, башкир и других народностей Российской империи отложились в коллекциях известных собирателей начала XX века – П.И. Щукина, И.Х. Колодеева, А.П. Бахрушина, П.Я. Дашкова и насчитывают более ста единиц хранения. Это жанровые и батальные сцены, виды городов, изображения представителей иррегулярной российской армии.

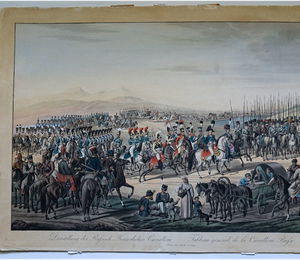

На рисунке под названием «Tableau général de la Cavalerie Russe» изображена русская кавалерия, включая иррегулярные войска, на марше.

Русская кавалерия. 1809 г.

Генерал в окружении штабных офицеров, трубачей, драгун, гусар, конной артиллерии прибыл на смотр иррегулярной кавалерии. Справа изображены уральские казаки, на переднем плане – башкиры, калмыки, маркитантка. И хотя гравюра неподписная, поиск аналогов в других музейных собраниях, в том числе зарубежных, помог установить имя автора оригинала. Им оказался немецкий художник Вильгельм фон Кобель, работавший для венского издательства в 1805–1813 гг. Среди многочисленных работ этого рисовальщика с изображениями французской кавалерии, прусской пехоты, прусских гусар и гренадеров, два листа были посвящены русской кавалерии. В гравюру рисунки Кобеля переводили немецкие художники Карл Раль (K.-H. Pahl) и Генрих Мансфельд (Mansfeld).

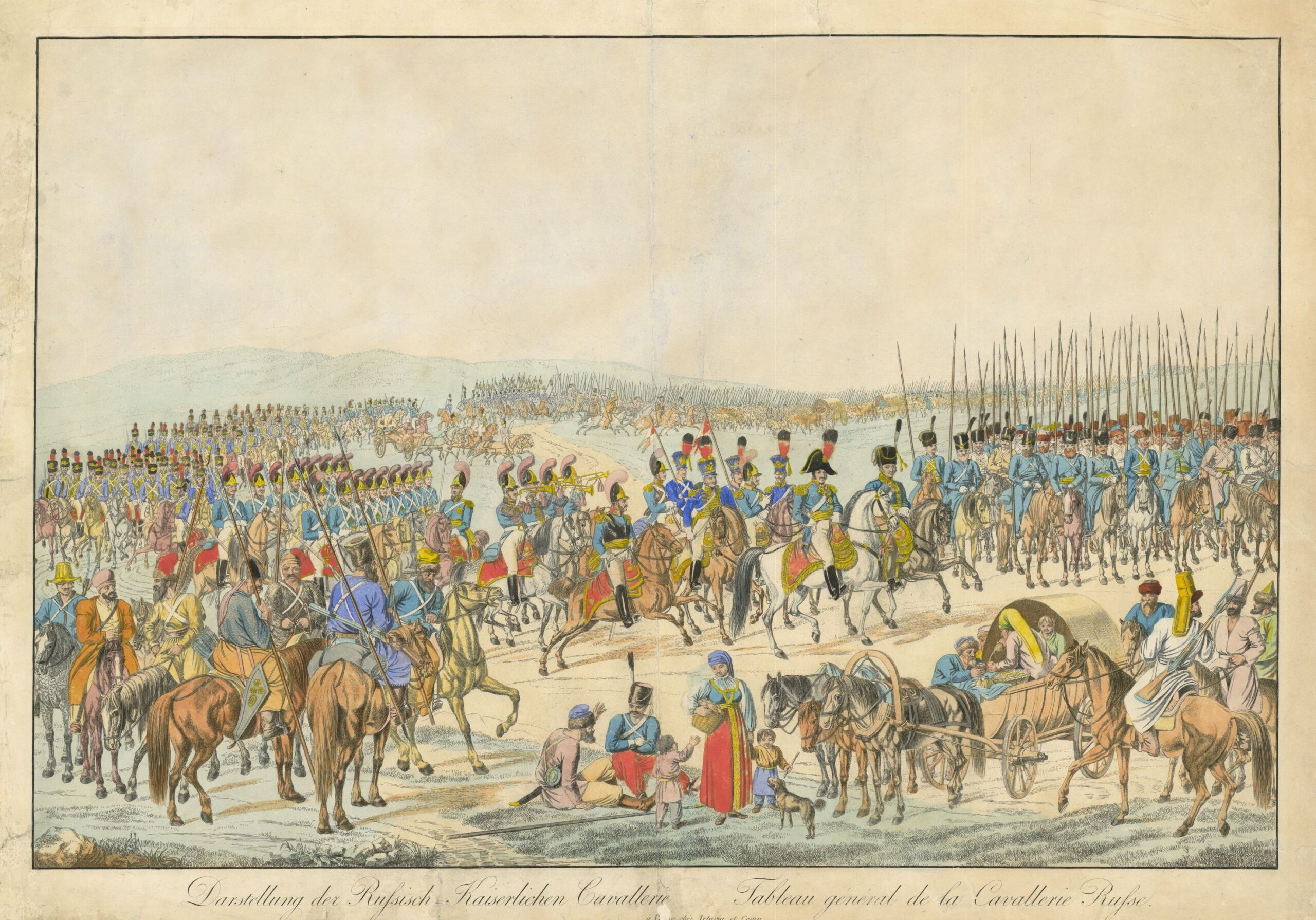

Еще один общий вид «Русской императорской кавалерии» запечатлен в гравюре акватинтой немецких художников первой четверти XIX века с изображениями нескольких представителей национальной конницы: крымских татар, черкеса, башкир, находящихся в одном отряде с гусарами. Гравюра была отпечатана в Берлине, в издательстве Гаспара Вейса.

Русская императорская кавалерия. 1813 г.

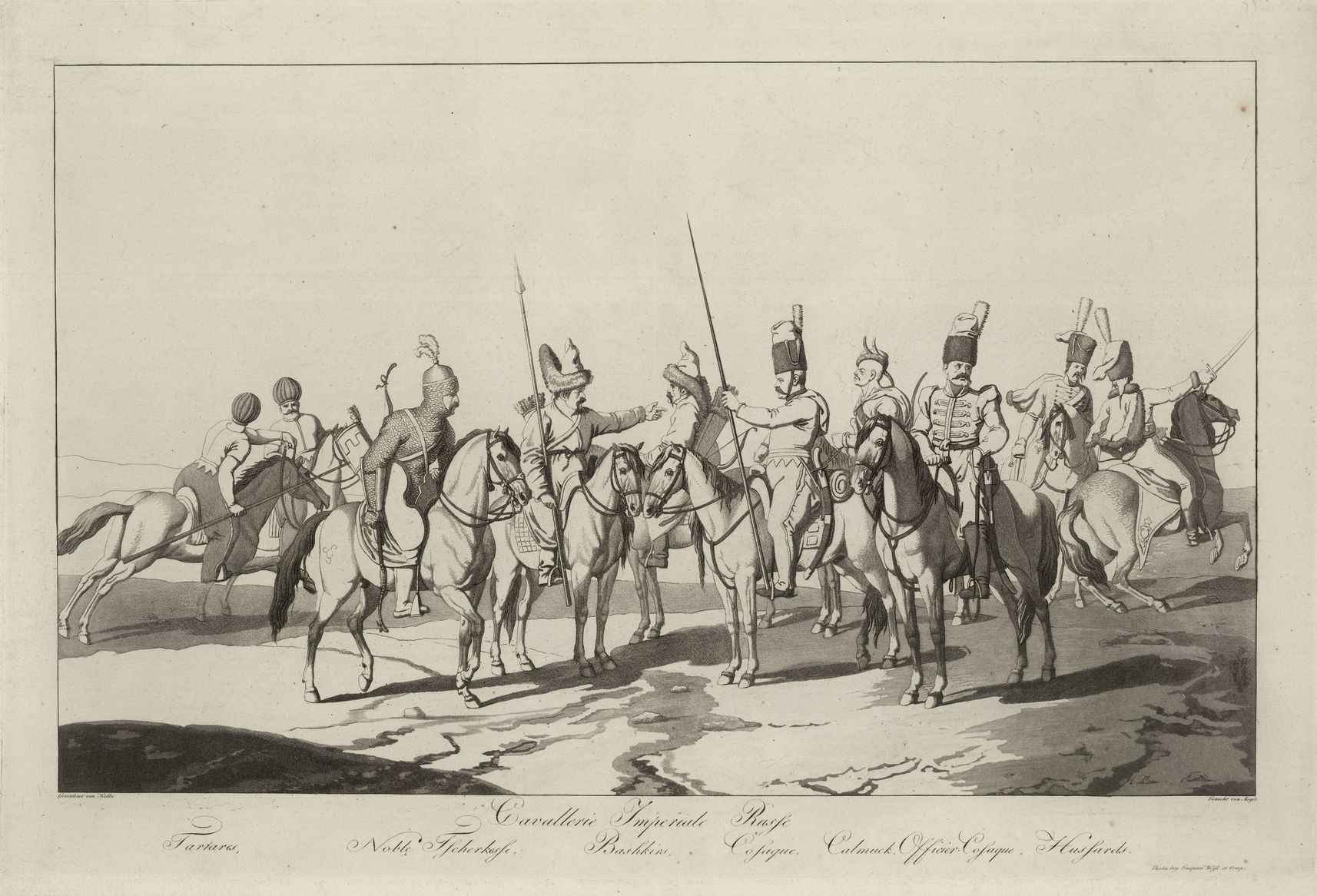

На графическом листе анонимного французского художника из собрания ГИМ изображена группа из трех всадников. Надпись под гравюрой поясняет, что рисунок сделан с натуры французским солдатом, изображены три офицера казака, захваченные в плен в последнем сражении вместе с оружием и багажом. Отметим допущенную неточность: на гравюре изображены два казака и один башкир, а не три казака, указанные в надписи.

Два казака и башкир. Первая четверть XIX в.

Такие неточности не так уж редки, особенно в графических листах, посвященных изображениям малых народов Российской империи, где калмыки идентичны башкирам, ногайцы татарам, а надписи не соответствуют действительности. В коллекции дореволюционного собирателя Колодеева сохранилась целая подборка небольших гравюр из одной серии «Russische Truppen», вышедшей в 1815 г. в парижском издательстве Поль-Андре Бассе. На графических листах запечатлены киргизы, калмыки, туркмены, татары, башкиры, черкесы. В основной массе эти листы не имеют авторских подписей, но имена некоторых художников нам известны. Это мастера французской национальной художественной школы – Бланшар, Дюбуа, Десре. Чем интересны их работы? Прежде всего, взглядом иностранцев на этнические группы народов Российской империи – их нравы и обычаи, костюмы, обмундирование. Не все народы участвовали в наполеоновских войнах, но иностранные художники во время своих путешествий по Российской империи, как например, Гейслер или англичанин сэр Роберт Кер Портер, любили их зарисовывать, особенно башкир.

Безусловным лидером по написанию башкирских всадников является Александр Осипович Орловский. Он был первым русским художником, кто запечатлел башкира задолго до событий 1812 года. В фонде произведений оригинальной графики отдела ИЗО ГИМ хранится рисунок Орловского «Башкир на лошади», на котором особенно заметно искусство рисовальщика подмечать мелкие детали в одежде, вооружении кочевых народов (колчаны со стрелами, налучья с луком, ватные халаты, высокие шапки с меховой опушкой или шапки-треухи – колаксыны).

Башкир верхом. 1818 г.

Бумага на картоне, итальянский карандаш, сангина

Рассматривая графику художников-современников, стоит обратить внимание на одну особенность – не всегда цветовая гамма на гравюрах соответствовала действительности, в большинстве случаев она произвольна. Это было связано с тем, что гравировали листы одни художники, а раскрашивали другие мастера в соответствии со своими знаниями или незнаниями цветовой гаммы униформы русских солдат.

Различие в раскраске гравюр хорошо заметно на двух парных листах, хронологически относящихся к событиям начала 1813 г., к примеру, на «Осаде русскими Данцига» и «Схватке казаков с французскими карабинерами при Мариенвердере». Эти гравюры были отпечатаны в Германии большим тиражом в первой четверти XIX в. и успешно продавались в Европе и России. Так, в 1911 году 25 листов из этой серии были приобретены московским Музеем 1812 года.

Конкретное участие национальной конницы в Битве народов не всегда отражено в документах, а вот в изобразительном искусстве тема Лейпцигского сражения была довольно популярной в творчестве многих художников, преимущественно немецких, изображавших казаков и национальную конницу.

Любопытна лубочная картинка неизвестного художника под названием «Достославное сражение при Лейпцыгъ октября 6-го 1813 года!» с расположенной под изображением обширной надписью на русском языке:

«Непонятно кажется какимъ образом Наполеонъ командовавший на 30-ти сраженияхъ и военною своею славою мнилъ затмить подвиги прежнихъ Полководцевъ,нъинъ поставилъ свою Армiю в столь невыгодную позицiю! Но Богъ в руцiъ коего Судьбы Царствъ и Народовъ полагаетъ конецъ неистовому стремленiе зла, Отъего всесильнаго изреченiя злое и коварное умышленiе приходитъ в замешательство до потерянiя разсудка. Онъ благоволилъ и Тиранъ вселенныя со всiъм адскимъ ухищренiемъ низвергается, и Его всещедрая Десница ниспослала отъ Престола своего крiъпкiя Силы союзнымъ и правовiърнымъ воинам».

Достославное сражение при Лейпциге октября 6-го 1813 года.

Первая четверть XIX в.

Другая гравюра с изображением битвы под Лейпцигом подписная, принадлежит мастерам немецкой школы Карлу Ралю и Иоганну Адаму Клейну.

Сражение при Лейпциге в октябре 1813 г.

Эти листы достаточно известны, поскольку выходили массовым тиражом в венском издательстве Artaria, в котором работали такие художники, как Генрих Мансфельд, Карл Шутц, Питер Краффт, Иоганн Зиглер и другие.

Зарисовывал с натуры события 19 октября 1813 года лейпцигский художник и гравер на меди Иоганн Якоб Вагнер (Johan Jakob Wagner, 1766–1834). Примечательно, что долгое время российские исследователи не могли идентифицировать имя художника, поскольку в это время в Лейпциге одновременно трудилось несколько художников с этой фамилией. Помогли установить «момент истины» коллеги из Лейпцига, указавшие на авторство сразу двух художников – Вагнера, как автора оригинала, и Иоганна Лоренцо Ругендаса, как гравера акватинтой.

Народное сражение при Лейпциге. 1813 г.

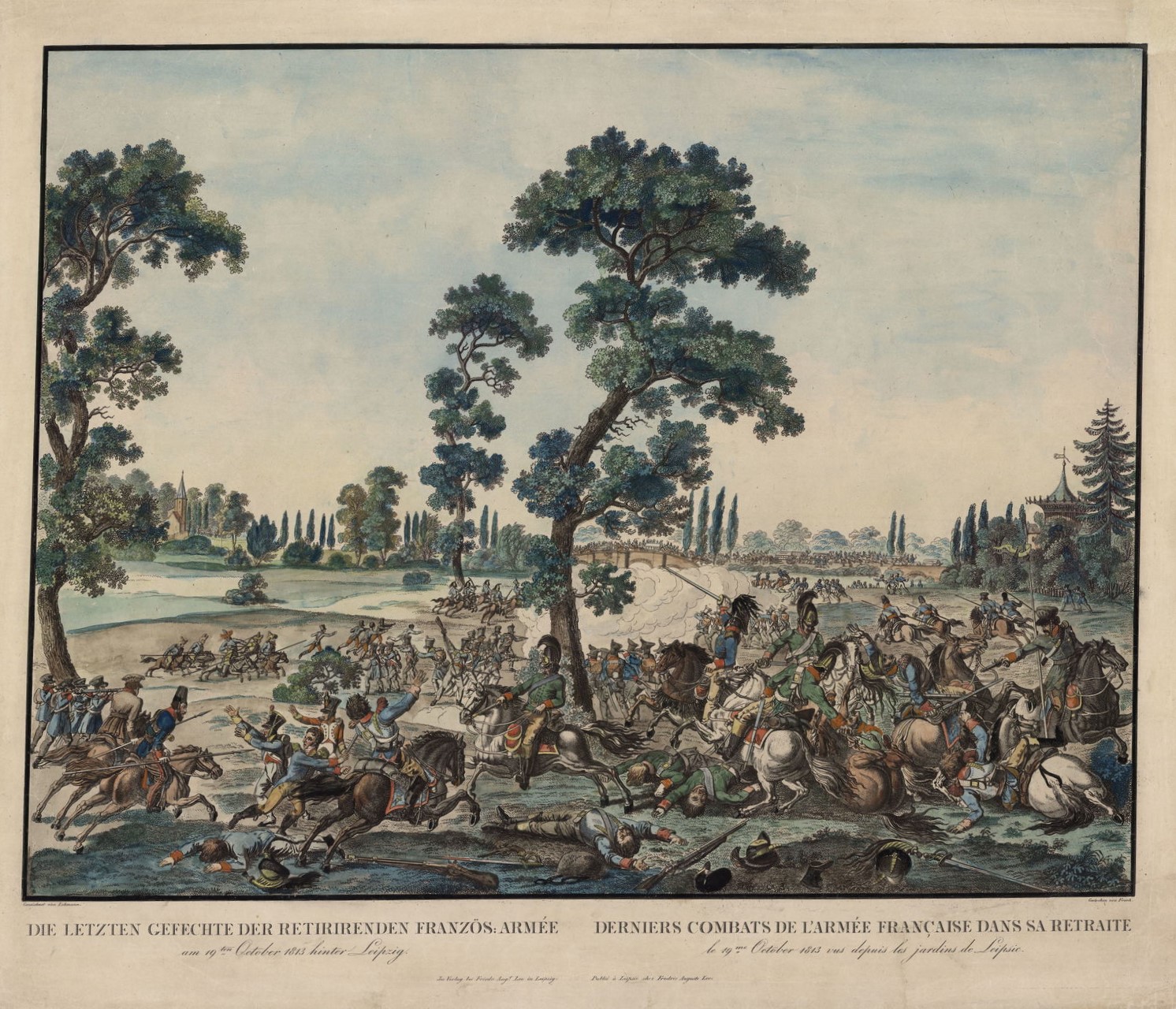

Очень эффектна своей яркостью и насыщенностью гравюра других немецких художников Фроша и Лехманна «Letzte Gefechte der sich zurückziehenden französischen Armee am 19. 10. 1813 in den Vorgärten Leipzigs», изобразивших события все того же дня 19 октября, но действие проходит на фоне городских садов.

Последние сражения французской армии 19 октября 1813 года в садах Лейпцига. Около 1820 г.

При некотором увеличении гравюры можно узнать на дальнем плане башкир, атакующих противника.

Помимо произведений печатной графики, в Историческом музее хранятся два оригинальных листа, посвященных событиям в Лейпциге. Один из них – эскиз неизвестного художника из собрания московского коллекционера А.П. Бахрушина и второй рисунок, густо раскрашенный акварелью и гуашью, подписной. Это работа немецкого художника-акварелиста Христиана-Готфрида-Генриха Гейслера (H.G.Geissler) «Сражение на Мясной площади в Лейпциге 19 октября 1813 года», на которой изображен эпизод середины дня 19 октября, когда все четыре союзных армии сошлись своими авангардами на Лейпцигской площади.

Сражение на Мясной площади в Лейпциге 19 октября 1813 года. 1813-1814 гг.

Бумага, акварель, гуашь, белила, тушь, перо

Не только батальные сцены были объектом внимания художников-современников. Интересна своей композицией жанровая гравюра английского живописца, рисовальщика и гравера Джона Августа Аткинсона (J.A.Atkinson), благодаря которому сохранились виды российских и европейских городов спустя короткое время после описываемых событий. На листе «Blick vom Grimmaischen Tor auf die Vororte Leipzigs» видна площадь пригорода Лейпциге – Гримма после сражения, заполненная ранеными, убитыми, группами казаков, собирающих трофеи.

Единственное живописное полотно из собрания Исторического музея, посвященное сражению при Лейпциге, принадлежит кисти одного из первых русских баталистов Владимира Ивановича Мошкова (1792–1839). Оригинальное название картины следующее:

«Сражение перед городом Лейпцигом на Вахаутских высотах между деревнями Конневиц и Либертвольквиц, бывшее 1813 года октября шестого дня, в присутствии их величеств императоров всероссийского и короля прусского, под предводительством главнокомандующего российско-прусскими армиями генерала от инфантерии М.Б. Барклая де Толли».

Сражение под Лейпцигом. 1815 г. (?)

Холст, масло

Картина поступила в фонды ГИМ из Военно-исторического музея в конце 1920-х гг., ранее хранилась в имении князей Барятинских Ивановском, в Курской губернии. В Санкт-Петербурге, в фондах Государственного Русского музея, находится еще один вариант этого полотна. По мнению реставраторов Отдела станковой живописи ГосНИИР, проводивших реставрационные работы и химико-технологическую экспертизу картины из собрания ГИМ, «московский» вариант Мошкова является эскизом к картине из собрания ГРМ. Реставраторы заметили также ряд униформологических неточностей, как то: горизонтальные полосы французских знамен, головные уборы французских пехотинцев, мундир прусского короля, блестящие кирасы русских кирасиров, нетипичное для французской армии сочетание красных доломанов и чикчир и т.д. Тем не менее, при проведении химико-технологической экспертизы полотна авторство В.И. Мошкова и датировка (1815) подтвердились.

Национальная конница русского царя приняла самое активное участие в наполеоновских войнах 1812–1814 гг. Для большинства ее представителей понятия чести и верности своему императору, своему Отечеству были не пустым звуком. Их участие в наполеоновских войнах воспринималось ими не как повинность, а как осознанная необходимость защиты родины. Выполняя свой воинский долг там, куда их поставило военное командование, они вместе с армией, казаками, ополчением, союзными войсками приближали час победы. Одним из ярких эпизодов такой борьбы была Битва народов под Лейпцигом.