Путеводитель по Берлинской Королевской фарфоровой фабрике

Королевская фарфоровая мануфактура в Берлине, также известная как Берлинская фарфоровая мануфактура

Фарфор KPM.

Королевская фарфоровая мануфактура в Берлине, также известная как Берлинская фарфоровая мануфактура, изделия которой обычно называют кратко берлинским фарфором.

Основана в 1751 году в Берлине В. К. Вегели́, а затем реорганизована в 1763 году королём Пруссии Фридрихом II Великим

Галереи керамики в Музее Виктории и Альберта в Лондоне - настоящая сокровищница для любителей фарфора. Хотя они наполнены культовыми предметами, такими как вазы эпохи Мин, голландская делфтская посуда и работы севрских и мейсенских мастеров, витрины этих галерей также являются домом для менее известных драгоценных камней.

Действительно, очень редко, спрятавшись в этом роге изобилия, вы можете наткнуться на мемориальную доску, чайную чашку или маленькую фигурку, изготовленную в KöniglichePorzellanManufaktur или KPM.

KPM была фундаментальной частью ландшафта европейского декоративно-прикладного искусства в 19 веке и была одним из самых плодовитых производителей роскошного фарфора в тот период.

Это было одно из самых инновационных и технологически изощренных предприятий своего времени, и его продукция соперничала с ведущими фабриками Европы. Так почему же он не стал более известным?

Что такое фарфор KPM?

KPM, или Königliche Porzellan Manufaktur ("Королевская фарфоровая фабрика" по-английски), является старейшей фарфоровой фабрикой Берлина и второй по старшинству в Германии. Компания была основана в 1763 году и продолжает производить фарфор по сей день.

В 18-м и 19-м веках компания KPM специализировалась на производстве фарфоровых обеденных сервизов, статуэток, расписных табличек, ваз и многого другого.

Они были особенно связаны с популярным стилем рококо середины 18-го века и с его заменой более строгим неоклассицизмом начала 19-го века.

Антикварные фарфоровые изделия KPM, относящиеся к этим периодам, сегодня широко коллекционируются и пользуются спросом.

На протяжении 18-го и 19-го веков KPM была одним из наиболее стабильно коммерчески успешных керамических предприятий Европы. Она также получила важную финансовую поддержку: сначала от прусской короны, а затем от объединенного германского государства.

Именно из–за тесных связей с государством название KPM - наряду с мейсенским – стало синонимом немецкого фарфора, так же как Севрский фарфор во Франции, Королевский фарфор Вустера в Англии и королевский фарфор Вены в Австрии.

История фарфора KPM

В отличие от своих кузенов-фабрик в Мейсене, Севре и Вене, попытки создать фарфоровую фабрику в Берлине не увенчались успехом. Первые две фабрики обанкротились, прежде чем, наконец, были переданы непосредственно королю Пруссии Фридриху II в 1763 году.

Берлин против Мейсена

Однако настоящие истоки KPM – как и всего европейского фарфора – лежат в саксонском городе Мейсен, первом месте в Европе, где был открыт секрет производства китайского "белого золота".

Все последующие европейские производители фарфора 18-го века появились на свет в результате попытки скопировать или украсть эту секретную формулу, известную как аркан.

Несмотря на то, что и Мейсен, и Берлин расположены на территории современной Германии, аркан не мог быть разделен между этими двумя местами из-за особенностей истории страны.

В 18-м и 19-м веках территория, которую мы сейчас называем Германией, на самом деле была несколькими разными странами: Берлин был столицей королевства Пруссия на севере, в то время как город Мейсен был частью Курфюршество Саксония дальше на юг. Эти два региона были соперниками.

К тому времени, когда два региона объединились в 1871 году, в них обоих уже давно действовали фарфоровые фабрики: именно по этой причине Германия сегодня может похвастаться тем, что KPM и Мейсен являются ведущими производителями керамики.

Ранний фарфор в Берлине

Первая попытка основать фарфоровую фабрику в Берлине была предпринята в 1751 году торговцем шерстью по имени Вильгельм Каспар Вегели. Вегели каким-то образом завладел "тайной" и предложил идею создания керамической фабрики королю Пруссии Фридриху II.

Король согласился и предоставил Вегели ряд королевских привилегий, включая освобождение от импортных пошлин и гарантию монополии в городе. Он начал работу по строительству фабрики на Фридрихштрассе в Берлине.

Однако фабрика Вегели вскоре развалилась: финансовые трудности, вызванные Семилетней войной, означали, что королевская финансовая поддержка больше не была столь надежной. Более того, во время войны прусская армия оккупировала город Мейсен, и поэтому король переключил свое внимание на производимый там фарфор.

К 1757 году Вегели обанкротился, а фабрика лежала в руинах. Его спас предприимчивый торговец Иоганн Эрнст Гоцковски, который купил запасы фарфора и нанял главного моделиста Wegely Эрнста Генриха Райхарда.

Гоцковский перевел фабрику на Лейпцигер-штрассе и добился ряда важных назначений, в том числе Фридриха Элиаса Мейера, ученика легендарного модельера Иоганна Иоахима Кандлера в Мейсене.

К сожалению, Гоцковски постигла бы та же участь, что и Вегели. Из-за разорительного финансового положения во время войны он не смог получить поддержку от государства, и в 1762 году фабрика снова закрылась.

Королевская фарфоровая фабрика, Берлин

Удрученный провалом берлинской фарфоровой промышленности, король Фридрих II, также известный как Фридрих Великий, предпринял решительный шаг и сам возглавил фабрику.

Он вложил большие суммы денег в новую фабрику и переименовал ее в Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin ("Королевская фарфоровая мануфактура Берлина"). Он также разрешил фабрике использовать ее ставшую знаменитой эмблему - свой королевский скипетр.

Новая фабрика также была на удивление прогрессивной в своем управлении. Работники получали выгоду от регулярного рабочего времени, достойной заработной платы, пенсий и коммунального здравоохранения – все это было практически неслыханно в середине 18-го века.

Фарфор KPM эпохи рококо

Фридрих II был поклонником нового стиля рококо в декоративно-прикладном искусстве и оформлял свои дворцы мебелью, украшениями и картинами в новом стиле.

Одним из первых его действий в качестве руководителя новой фабрики KPM было заказать обеденный сервиз, соответствующий его роскошным интерьерам: Reliefzierat, как его называли, был украшен позолоченным рельефным орнаментом, чтобы он соответствовал лепным рельефам в столовой. комнаты в Новом дворце в Потсдаме.

Другие известные обеденные сервизы периода рококо от KPM включают модели Neuzierat, Neuglatt и Rocaille – все они были заказаны Фридрихом II для своих дворцов или были подарены в качестве дипломатических подарков. подарки. Эти конструкции все еще находятся в производстве по сей день.

Одним из наиболее новаторских достижений фабрики KPM в этот ранний период была разработка технологии получения светло–голубой фарфоровой глазури - в отличие от более жесткой, темной кобальтово-синей, которая преобладала ранее.

Этот новый цвет был известен как bleu mourant ("умирающий синий") и, опять же, был разработан для того, чтобы соответствовать интерьерам дворцов Фридриха в Потсдаме. Его можно было бы использовать для украшения обеденного сервиза Neuzierat.

Неоклассический фарфор KPM

Фридрих Великий умер в 1786 году, и под руководством его преемника Фридриха Вильгельма II (его племянника) фабрика изменила стилистическое направление, чтобы принять формирующийся неоклассический стиль.

За эти годы на фабрике произошло несколько изменений: были построены новые печи для обжига, чтобы максимально повысить эффективность и качество; были разработаны новые оттенки зеленого; а в 1797 году был установлен первый в Берлине паровой двигатель.

КПМ также начала нанимать известных немецких художников для моделирования и раскрашивания своих изделий: к ним относились художник Карл Фридрих Шинкель (1781-1841), скульптор Иоганн Готфрид Шедоу (1764-1850) и скульптор Кристин Даниэль Раух (1777-1857).

Шедоу, например, изготовил оригинальную гипсовую модель для знаменитой группы принцесс КПМ; в то время как Раух спроектировал ряд важных ваз в неоклассическом стиле для фабрики; а Шинкель разработал знаменитую "сахарную корзинку" для королевы Луизы Прусской.

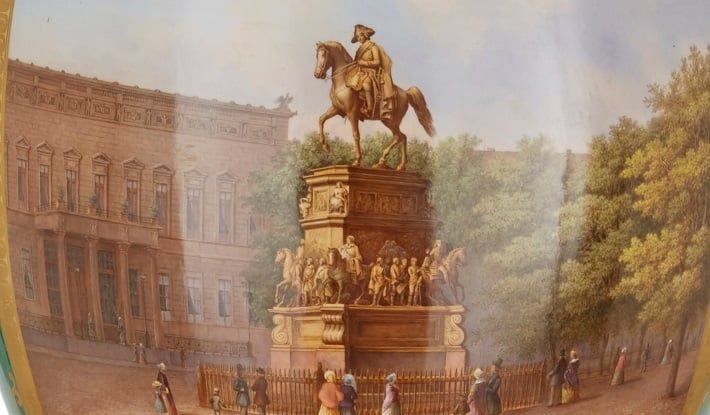

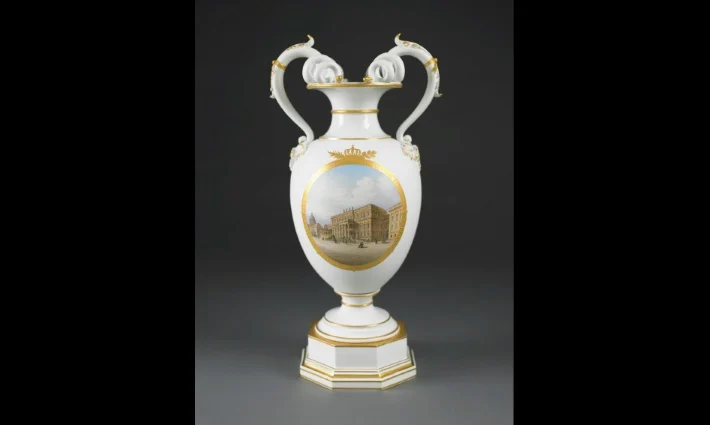

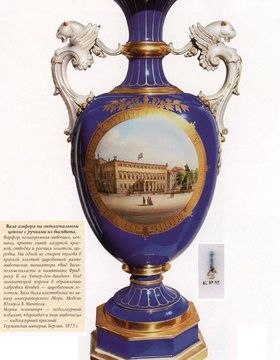

Именно в этот период конца 18-го и 19-го веков КПМ прославилась своими картинами ведута (высокодетализированные крупномасштабные пейзажи земли, города и моря), которые она наносила на фарфоровые таблички, посуда и вазы. Вы можете увидеть великолепный пример этого на картинке выше.

На этих ведутах часто изображались виды Берлина, и как таковые они стали важными сувенирами для гранд-туров, а также полезными дипломатическими подарками. Прекрасные ведути КПМ сыграли решающую роль в укреплении репутации Берлина как города в 19 веке.

КПМ в 19-м веке

На протяжении оставшейся части 19-го века KPM продолжала внедрять инновации и производить изысканные фарфоровые сервизы, вазы и статуэтки.

Фабрика также продолжила производство старых моделей и изделий, которые стали популярными среди правящего класса Европы.

Одной из особенно отличительных разработок фабрики КПМ в 19 веке был широкий ассортимент фарфоровых табличек, которые она производила.

Многие из них были потрясающими копиями картин старых мастеров, а также важных полотен немецких художников. Некоторые из них были даже оригинального дизайна, и все таблички KPM были расписаны ведущими фарфоровыми копиистами того времени.

Арт-нуво, баухауз и современный фарфор KPM

КПМ продолжала внедрять инновации на протяжении всего 19-го века и в современную эпоху. В 1867 году фабрика переехала в связи со строительством нового здания прусского парламента.

Теперь новая фабрика расположена на реке рядом с парком Тиргартен, и все ее товары можно было бы перевозить через весь город на лодке.

В 1878 году КПМ основала Химико-технический институт под руководством химика Германа Августа Сегера, чтобы более внимательно изучить науку о фарфоре.

Именно в результате этого развития KPM заняла лидирующие позиции в области технических инноваций в керамике, разрабатывая новые цвета глазури и эмали, которые будут использоваться для создания новых дизайнов.< / p> Эти технологические разработки совпали с развитием нового стиля ар-нуво (или югендстиля, как его называли в Германии). Великий период югендстиля KPM начался в 1908 году под руководством Теодора Шмуц-Бодисса, который использовал новую глазурь Сегера для создания некоторых исключительных изделий в стиле ар-нуво.

По мере развития 20-го века дизайнеры KPM начали испытывать влияние идей Баухауза и так называемых школ архитектуры и дизайна ‘Новой объективности’. Продукты KPM развивались соответствующим образом.Остальная часть 20-го века была неспокойным временем для фабрики: ее здания были разрушены во время воздушного налета в 1943 году и не возвращались на свое место в Тиргартене до 1957 года, когда производство продолжилось.

Как идентифицировать фарфор KPM

Таким образом, продукция KPM претерпела значительные изменения в стилях и техниках. В изделиях KPM нет единого декоративного стиля, который выделял бы их как узнаваемые ‘KPM’.

Изделия KPM, однако, тщательно проштампованы и маркированы, чтобы подтвердить их подлинность.

На что обратить внимание показано ниже.

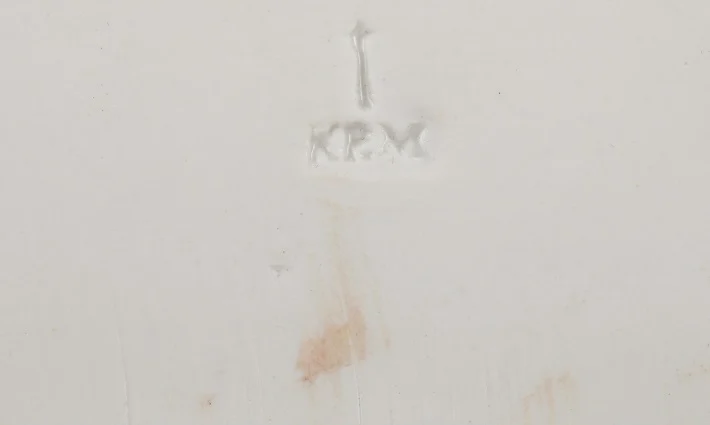

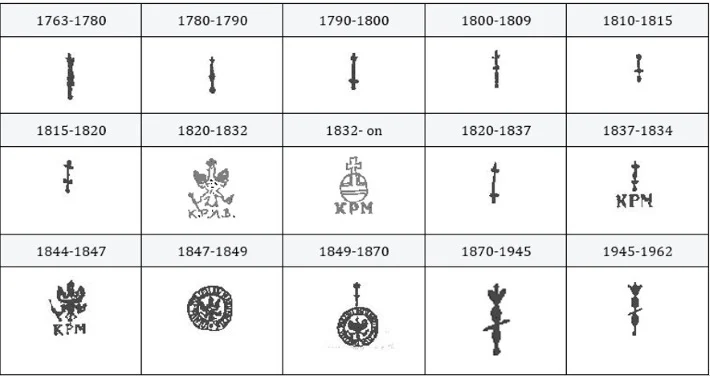

Марки фарфора KPM

Самой четкой маркировкой на изделии из фарфора KPM всегда будет знак скипетра, который используется с момента основания фабрики.

Изделия до производства KPM, произведенные на фабрике Wegely, будут помечены буквой "W", в то время как изделия, произведенные в Gotzkowsky, будут помечены буквой "G’.

Вызывает недоумение тот факт, что некоторые из самых ранних маркировок Мейсенской фабрики на своих изделиях (примерно до 1730 года) содержали буквы "K.P.M", или KöniglichePorzellanManufaktur (Королевская фарфоровая мануфактура)., поскольку Мейсен также был королевской фабрикой. Эти марки не следует путать с марками берлинской KöniglichePorzellanManufaktur.

С 1837 года под знаком скипетра были добавлены буквы "КПМ", а в середине 19-го века скипетр часто появлялся со знаком орла.

Такие знаки, как скипетр, орел и надписи KPM, обычно наносятся вручную кобальтово-синим цветом на белый фарфор и коричневым - на расписной фарфор. Исключением из этого правила являются фарфоровые таблички 19-го века, на которых знак (обычно скипетр с буквами "КПМ") будет оттиснут, а не нарисован.

Помимо торговой марки KPM, изделия KPM также будут украшены знаком имперского шара, цвет которого зависит от типа украшения на изделии.

Красный шар указывает на цветочную роспись, фигуративные сцены и пейзажи, в то время как зеленый шар указывает на любой другой тип декора; а синий шар указывает на украшения на изделиях, которые были обожжены при высоких температурах (совет: изделия с синим шаром можно мыть в посудомоечной машине!).

Наконец, на любых нарисованных сценах также будет подпись художника, обычно коричневого цвета.

Фарфоровое искусство и антиквариат KPM

Благодаря своей 250-летней истории фабрика KPM произвела огромное количество фарфора для самых разных клиентов.

Некоторые модели были изготовлены по индивидуальному заказу, в то время как другие находились в постоянном производстве для массового рынка. Ниже представлены наиболее известные продукты и дизайны KPM.

Фарфоровая чашка KPM в стиле ар-нуво, 1902 год, дизайн Адольфа Флэда

Обеденные сервизы KPM были их самыми известными и успешными продуктами. В 18 веке король Фридрих II заказывал на фабрике обеденные сервизы, и именно в создании новых дизайнов посуды проявились первые инновации KPM.Фредерик заказал в общей сложности 21 сервиз для ужина: в каждом было до 500 предметов, и в нем могли разместиться 36 гостей.< / p> Самыми известными обеденными сервизами KPM 18-го века были сервизы Rocaille, Neuzierat, Neuosier и Neuglatt, все они были заказаны Фредериком. Нойзират был знаменит своим оттенком "bleu mourant", который он использовал; Рокайль - орнаментом в стиле рококо; Нойозье - своей плетеной структурой (от французского "ива", что означает "ива’).Возможно, самым большим успехом неоклассического периода KPM стал обеденный сервиз, который они разработали для Питера фон Бирона, герцога Кирландского, в 1790 году. И снова эта услуга, известная как Kurland, остается в производстве и по сей день.Фарфоровые фигурки KPM

С конца 18-го века KPM также специализировалась на производстве фигурок мелких животных для более широкого рынка.

Некоторые из наиболее известных произведений KPM из скульптурного фарфора включают Prinzessinengruppe, которая была спроектирована Иоганном Готфридом Шедоу и была изготовлена в 1795 году в память о двух королевских свадьбах, которые состоялись в Пруссии в том году.

Еще одна известная скульптурная работа KPM известна как Свадебная процессия, изображение выше, и была завершена в 1908 году в ознаменование свадьбы прусского наследного принца Фридриха Вильгельма в 1905 году.

Первоначально центральное украшение было спроектировано скульптором Адольфом Амбергом и выполнено из серебра, но от идеи отказались, пока ее не подхватил Теодор Шмуц-Баудисс, директор KPM.

Статуэтки производились до 1930-х годов, а оригинальное изделие принесло KPM золотую медаль на Всемирной выставке 1910 года в Брюсселе.

Фарфоровые таблички KPM

Фарфоровые таблички, часто копирующие работы старых мастеров или более поздние немецкие картины, были значительной частью продукции фабрики в 19 веке.

У KPM был целый отдел, занимавшийся копированием картин на фарфор, и эти изделия стали чрезвычайно популярными среди растущего класса потребителей, поскольку они предлагали альтернативу дешевым, некачественным раскрашенным копиям старых мастеров, доступным на рынке.

Чем больше была мемориальная доска, тем технически сложнее ее было изготовить и, следовательно, тем более ценной она была.

Фарфоровые вазы KPM

Аукцион искусства и старины art-picture.ru предоставляет возможность покупки

приобрести представленны лоты по теме "Путеводитель по Берлинской Королевской фарфоровой фабрике"

Ваза-амфора на октаго…

Ваза-амфора на октаго… Статуэтка собаки Герм…

Статуэтка собаки Герм… Фарфоровая фигура "Се…

Фарфоровая фигура "Се… Тарелки KPM Германия

Тарелки KPM Германия Тарелка военная кабин…

Тарелка военная кабин… Чашка с блюдцем с изо…

Чашка с блюдцем с изо… Художественная тарелк…

Художественная тарелк… Канделябр в стиле нео…

Канделябр в стиле нео… ЧАШКА С БЛЮДЦЕМ С ИЗО…

ЧАШКА С БЛЮДЦЕМ С ИЗО… ВАЗА НА ОКТАГОНАЛЬНОМ…

ВАЗА НА ОКТАГОНАЛЬНОМ… Тарелки KPM Германия

Тарелки KPM Германия Старинный коллекционн…

Старинный коллекционн… Тарелки обеденные KPM…

Тарелки обеденные KPM… Чашка с блюдцем с изо…

Чашка с блюдцем с изо…